Piercingly bright yet implausibly small, light-emitting diodes—or LEDs, to use their somewhat catchier nickname—are having an outsize influence on interior design. These energy-efficient light sources, which require a fraction of the electricity of incandescent and even the much-loathed compact-fluorescent bulbs, aren’t just giving stressed-out environmentalists reason for optimism. They’re also freeing designers to reinvent lamps—and light itself—in ways that once seemed impossible.

“It’s similar to what happened in the ’80s, when halogen arrived: Everything became smaller,” said Piero Gandini, chairman of Flos, a design-driven lighting company. But Mr. Gandini predicts that the impact of the LED will be more dramatic: “Design will be less and less about the fixture itself and more about the immaterial aspect of lighting.”

Here are five talking points about this game-changing light source that you’ll want to memorize in case you attend a cocktail party entirely populated by futurists, or just want to know how LEDs are going to affect your living room, your kitchen and the way you read yourself to sleep.

The incredible shrinking light bulb

LEDs are tiny and thin—often about the width of a pencil eraser—which is letting designers give all sorts of light fixtures a nip and tuck. Take, for example, the old-school banker’s lamp, typically a rather hulking presence. By replacing the standard bulb with a slender strip of warm white LEDs, Ron Gilad created a sleeker version, his Goldman lamp for Flos. Given the petiteness of LEDs, he was able to replace the traditionally bulky shade with a sliver of injection-molded plastic and considerably whittle down the brass base, since it no longer needs to support a hefty top. His lamp reads like a suit tailored for a particularly slim banker. “If we were using an incandescent bulb, we would not be able to reach the same level of minimalism,” said Mr. Gilad.

Coolness under pressure

Unlike traditional light sources, the surface of an LED is cool to the touch, which means you can tuck them into tight spaces without heating up surrounding surfaces. In-the-know kitchen designers, for instance, are mounting strips of LEDs under upper cabinets to illuminate the countertop without inadvertently slow-roasting any food stashed inside cupboards. Architect David Rockwell installs LED fixtures directly into the perimeters of floors to uplight walls. While scorching incandescent lamps can discolor surrounding materials, like drywall and wallpaper, he explained, “with LEDs, you don’t have the heat issues.”

The coolness factor is also contributing to the continuing slenderization of lamps. The shade of Flos’s Goldman, for example, sits very close to the light source, mainly because it can. And while Isamu Noguchi’s circa-1950s paper lanterns—voluminous, semirigid globes—were designed to keep the paper far away from the incandescent bulb, the soft shade of their intricately folded descendant, Issey Miyake’s new LED-equipped Mendori, can be stretched or compressed like an accordion, coming into proximity to the bulb with little risk of combustion.

Power in a snap

LEDs’ energy efficiency may please the eco-conscious and the environmental regulators, but the lights’ meager appetite for electricity also offers a distinct aesthetic advantage: It allows wires to be thinner and less thickly insulated. With certain LED chandeliers, the power cord is indistinguishable from the thin cables suspending the fixture from the ceiling. The word “floating” is frequently invoked.

This characteristic is also letting designers embed LEDs in paper-thin materials, creating wallpaper, for instance, that’s studded with dim points of light. In such cases, the “wires” have been reduced to a very thin conductive material. To create its Abyss wallpaper collection, released this month, London-based Meystyle applies the material by hand; Ingo Maurer’s LED Wallpaper goes a step further: A conductive ink is printed directly on the paper.

The ease of powering LEDs also allows designers to “daisy chain” lights—kind of like attaching one string of Christmas tree lights to another. Luceplan took advantage of this when creating its Synapse system, a module-based approach to room dividers. Each star-shaped piece, illuminated by a color-adjustable LED, snaps together with the next, providing electricity to the others connected to it. The result: a glowing web of stars that can subtly divide a living room from a dining room.

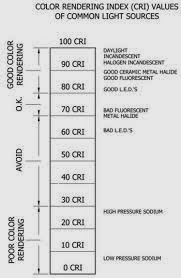

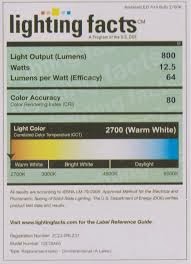

Chameleonic color

Perhaps the most powerful new tool that LEDs offer lighting designers is the ability to adjust the color temperature of white light. A controllable feature known as “dynamic white” offers almost as many minute variations on paleness as Benjamin Moore does with paint.

Dynamic white fixtures contain arrangements of warm and cool white LEDs, and achieve their effects by delivering different blends of the respective light, explained lighting designer Linnaea Tillett, who has illuminated spaces created by architects including Maya Lin and Diller Scofidio + Renfro. “It’s amazing how much subtlety and finesse they provide,” said Ms. Tillett. “You can change the whole emotional tone of a room using the same light fixture.”

For one client with a windowless room, Ms. Tillett set a dynamic white LED on a timer to cast a pure, sunlight-like glow early in the day that gradually became more golden in the afternoon. “Particularly in windowless rooms, it allows you to create a sense of the passage of time,” she said.

Although this feature is primarily available in products aimed at architects and interior designers, it is trickling down to the consumer level. Luceplan’s Curl lamp, for example, has a phosphorous lens that lets you shift the color temperature of the 8-watt lamp from a warm 2400K to a cooler 3500K by twisting a dial.

The hackable light

LEDs are essentially light-producing semiconductors—which means it’s increasingly easy to build “smart” features directly into the light source itself. “With LED, we are moving from electrics to electronics,” said Mr. Gandini of Flos. He predicts that lamps will eventually be able to interact with their surroundings, perhaps by tuning their color temperature and brightness levels to settings triggered by the presence of an individual’s smartphone. (Some of his company’s lamps already have built-in occupancy sensors, as well as sensors that adjust the intensity of a beam depending on the ambient light levels in a room.)

Innovation is accelerating. “In the past, there were only three or four good suppliers of traditional light sources in the world,” said Mr. Gandini. But because of LEDs’ overlap with the semiconductor industry, he added, a wide range of electronics companies, especially in Asia, are now manufacturing them—and each is contributing its own ideas on how light and electronics can be integrated.

On a smaller scale, the open-source movement is letting independent designers deliver advanced features that previously would have required an engineering team to execute. The Dim(some) Phonezone chandelier, by Brooklyn-based designer Brendan Keim, incorporates eight LEDs that can be controlled individually with a smartphone app—a trick Mr. Keim was able to pull off using an open-source electronics platform called Arduino. “It’s very accessible for artists and designers to jump into,” he said. “Anyone who is familiar with Arduino could hack this lamp. You could make the LEDs twinkle or fade light from one side to another.”

The technological potential of LEDs is only beginning to be realized. “It’s about the evolution of software and control gear,” said Mr. Gandini, “but also our cultural imagination.”

Please visit us at

www.fogglighting.com and be sure to call with all your lighting questions and needs.